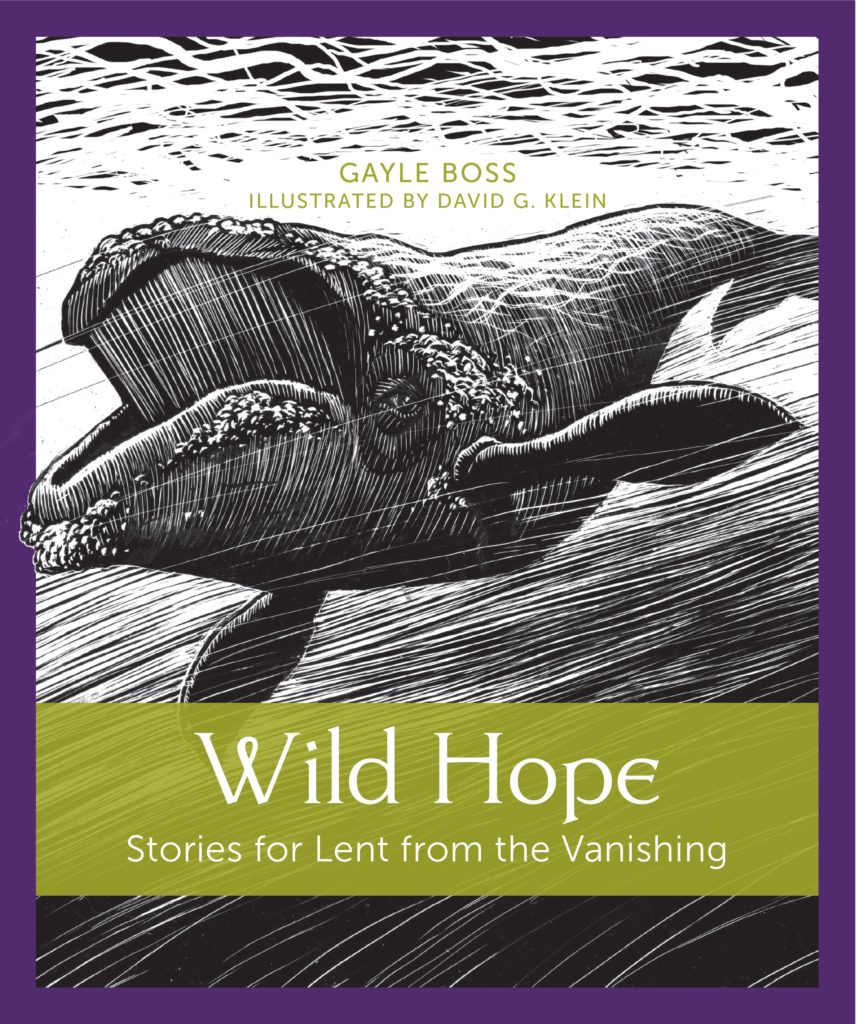

My friend Jon Terry from the Au Sable Institute sent me a surprise gift in the mail – a copy of the book Wild Hope: Stories for Lent from the Vanishing by Gayle Boss. The book has six sections for the six weeks of Lent. Each section features the profiles of four animals, from the Chinese pangolin and black-footed ferret to the Amur leopard and golden riffleshell mussel. Each profile opens your eyes and heart to the wondrous qualities of the animal. Gayle also shares, in an understated yet poignant way, the challenges each species faces to survive.

Because Gayle is such a gifted writer, it’s hard to resist sharing a multitude of excerpts. Here are two from her introduction that get to the purpose of Wild Hope:

“Attention to the amazingness of our arkmates routes us directly to the heart of Lent. The season means to rouse us from our self-absorption.”

“The promise of Lent is that something will be born of the ruin, something so astoundingly better than the present moment that we cannot imagine it. Lent is seeded with resurrection. The Resurrection promises that a new future will be given to us when we beg to be stripped of the lie of separation, when the hard husk suffocating our hearts breaks open and, like children, we feel the suffering of any creature as our own. That this can happen is the wild, not impossible hope of all creation.”

I highly recommend this book for you and your family. You will more deeply treasure God and God’s Creation. Your heart will also go out to the men and women who are dedicating their lives to preserve the life of God’s earth. Gayle’s writing will affirm your own convictions and heart for the life around us. You’ll be struck by the beautiful art of David G. Klein. And the book will move your heart in new ways during this Lenten season

I’m grateful to Gayle for writing this book. She generously took time to respond to four questions I had for her.

Nathan: You write in the introduction to Wild Hope, “I didn’t hear all creation groaning when my sons were young. I was oblivious to the millions dying, their kinds never to be seen on the earth again.” Can you share how you came to be a Christian, a writer, and a Christian writer called to communicate about the life of God’s earth?

Gayle: I grew up in a church-going family (the Dutch Reformed tradition) and loved all-things-church, even as a teenager! It seemed to me the one public place where what really mattered—who we are and why we’re here—got talked about. That impulse to talk about what matters also drew me into a writing life.

I’ve tried my hand at nearly all creative literary forms, from long-form journalism to haiku. In my early forties I wrote a 535-page failed novel. The wish to write about animals and how close bonds with them make us more deeply human grew on me so slowly I’m not sure I can trace it.

This much seems true: When my sons were young, their love of animals woke a long-dormant attention to animals in me. I remembered how I would cry when my father and uncles hung up deer they’d shot from the branches of a big oak tree to bleed out. And I remembered how the rest of the family laughed at my tears. The venison was part of our winter food supply, my food supply, too.

Led by my children, I let my original tenderness for animals rise again. I noticed how good that felt, even when I experienced an animal suffering. I felt more alive, more free. I now believe that’s because I reconnected with the One Love planted in all things at their creation; the love at my core calls to the love at their core. Restoring that connection is a path back to our deepest selves and back to the beloved community of all created things that we call Eden or The Peaceable Kingdom, where “They will not hurt or destroy in all (God’s) holy mountain.”

Nathan: Please share what your goals were for Wild Hope and why you believe attentiveness to “..the amazingness of our arkmates routes us directly to the heart of Lent.”

Gayle: As with All Creation Waits, I wanted to wake, or fan, in readers the kind of love for animals that was dormant for so long in me—a love that doesn’t “cute-ify” them, but sees each one as “a word of God and a book about God,” as Meister Eckhart said. In that first book, I wrote about animals that many of us see regularly, like skunks, raccoons, and chickadees.

In Wild Hope, I describe animals most of us will never see in the wild, from orangutans to olms. I wanted to describe their magnificence and tell their stories, including the stories of their suffering on a planet we’ve made unlivable for them. I thought that if I could tell their stories in such a way that we readers would be drawn into their worlds, our defenses could melt, and we could grieve their suffering. We could see them as expressions of God’s own self and God’s own suffering—at our hands. Which is the white-hot core of Lent.

It’s important to me that we readers respond to the animals’ stories first with love, not shame and guilt. Because we’ll only make the radical life-changes that will protect the earth for all animals, including us, if we’re motivated by love. Guilt-motivated change may work for the short term, but it can’t be sustained. Over the long haul, we only protect and save what we love.

Nathan: What animal of God’s earth most captivates your heart? Why?

Nathan: What animal of God’s earth most captivates your heart? Why?

Gayle: Of course you know that I’m going to say I’m smitten by every animal I see and learn about. And it’s true, I really am!

The “episode” of each animal’s story that most undoes me, though, comes when, faced with impending death, they desperately do everything in their power to protect their young. While researching and writing Wild Hope, I saw that episode occur over and over: The mother polar bear struggling to keep her cubs afloat in seas without ice floes, and failing; Laysan albatrosses watching their chicks sink into lethargy from plastic poisoning, and die; the pangolin mother curling around her baby when the poacher pulls her out of her den. As a mother, to recognize that my actions, our actions, inflict the worst suffering I can imagine on other mothers was almost more than I could bear.

Learning the stories of these animals swelled my love for them, and love wouldn’t let me look away from their suffering. It made me fiercer in my commitment to change parts of my life that contribute to their suffering. We only protect and save what we love.

Nathan: What role do you believe art can play in inspiring Christians to understand God’s love for the whole world (including our “nonhuman kin”), to act on that understanding, and to somehow work through the despair and grief we experience as we see our nonhuman kin suffering?

Gayle: I don’t believe we’ll ever “understand” God’s love for all created things. Understanding is a motion of the mind, and God’s love for all things is way beyond our minds. It can happen, though, that we’re grasped by God’s love for all created things. Somehow, that “beyond us” Love that created the universe finds an opening in the hard husk of our egos and “cuts us to the heart,” as It did those who heard Peter tell the Jesus-story at Pentecost. Once Love has got hold of our hearts, it changes how we see everything. And when we see differently, we behave differently. “If your eye is good, your whole body will be full of light,” Jesus says.

At their best, stories, visual art, dance, and music bypass the mental constructs we use to defend ourselves and our walled-off ways of living. True art is the dart Divine Love uses to cut to our hearts. Suddenly or slowly, it reveals a new way of perceiving a world we thought we knew. Think of how differently the night sky appears once we’ve been struck by Van Gogh’s “The Starry Night.” What was static is suddenly full of energy and motion and presence.

It’s important to say that art doesn’t always pierce our thick husks with what we find beautiful. Sometimes art seems ugly or threatening, troubling. Van Gogh’s neighbors did not think “The Starry Night” was beautiful. They thought he was a crazy man making unpleasant, offensive paintings – that’s how new his way of perceiving was.

But for those of us who can allow even a crack in our armor, God can use art to peel the scales from our eyes and show us a universe pulsing with Presence, with creative energy unbounded. That vision becomes so compelling, we want to do everything we can to make ways for God’s always-creating energy to manifest in the visible world. “Working for change” isn’t a burden we bear but a dance we cannot help but do. As Paul says in the fifth chapter of Romans, “We rejoice in the hope of sharing in God’s glory.”

At the same time, we also suffer more deeply with the suffering. But as Paul goes on to say, “We rejoice in our sufferings,” because somehow suffering leads to a hope that “does not put us to shame, because the love of God has been poured into our hearts through the Holy Spirit.”

My limited experience tells me that in suffering we sink more deeply into the heart of God, into the Love that is at the core of the Universe—at our core—and know ourselves to be truly alive. Sunk in that Love, we also know that it is the truest thing in the universe—it’s the origin of the universe—and that Love cannot but have the final say. We carry on in the irrepressible hope that God is the one “who gives life to the dead and calls into being the things that are not.” (Romans 4:17)

That’s the Wild Hope at the center of the book Wild Hope: Stories for Lent from the Vanishing. I hope the stories reveal the pulsing presence of God in each creature and the drive of Love for that creature to survive. That’s a drive I want to join.